- 2-1-1

-

http://www.211.org/

2-1-1 is an easy to remember telephone number that, where available, connects people with important community services and volunteer opportunities. United Way chapters across America are spearheading the implementation of 2-1-1.United Way of America and the Alliance for Information and Referral Systems strongly support federal funding so that every American has access to this essential service.

- American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD)

-

http://www.aamr.org/

AAIDD is an organization that promotes policies, information, and human rights for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Also see disability resource list at http://www.aamr.org/content_2383.cfm?navID=2

- American Foundation for the Blind (AFB)

-

http://www.afb.org/

A nonprofit organization that advocates for the blind or visually impaired in the United States.

- American Red Cross

-

http://www.redcross.org/

The American Red Cross offers humanitarian care to the victims of war and aids victims of devastating natural disasters. Over the years, the organization has expanded its services, with the aim of preventing and relieving suffering.

- Area Agency on Aging (AAA)

-

http://www.n4a.org/

The AAA provides local services that make it possible for older individuals to remain at home, preserving their independence.

- Area Health Education Centers (AHEC)

-

http://www.nationalahec.org/home/index.asp

The AHEC (Area Health Education Centers) program was developed by Congress in 1971 to recruit, train and retain a health professions workforce committed to underserved populations. Together, with the Health Education and Training Centers program, helps bring the resources of academic medicine to bear in addressing local community health needs. By their very structure, AHECs and HETCs are able to respond in a flexible and creative manner in adapting national health initiatives to the particular needs of the nation’s most vulnerable communities.

- Asian and Pacific Islander Health Forum (AAPIHF)

-

http://www.apiahf.org/

A national advocacy organization that promotes policy, program, and study to improve the health and well-being of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities.

- Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)

-

http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/

CDC’s BRFSS is the world’s largest, on-going telephone health survey system, tracking health conditions and risk behaviors in the United States yearly since 1984. Conducted by the 50 state health departments as well as those in the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands with support from CDC, BRFSS provides state-specific information about issues such as asthma, diabetes, health care access, alcohol use, hypertension, obesity, cancer screening, nutrition and physical activity, tobacco use, and more. Federal, state, and local health officials use this information to track health risks, identify emerging problems, prevent disease, and improve treatment.

- BRFSS Operational and User’s Guide

-

http://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Data/Brfss/userguide.pdf

The User’s Guide is a manual covering all aspects of BRFSS survey operations and includes information on many aspects of the BRFSS survey that can help you as you develop survey tools and need to train people to conduct telephone surveys.

- CDC Emergency Preparedness & Response

-

http://www.bt.cdc.gov/

This site is intended to increase the nation’s ability to prepare for and respond to public health emergencies. This site provides information on preparing for specific hazards such as bioterrorism, chemical emergencies, radiation emergencies, mass casualties, and natural disasters and severe weather.

- Centers for Independent Living (CIL)

-

http://www2.ed.gov/programs/cil/index.html

CILs are non-residential, private, and CBOs that provide services for individuals with all types of disabilities. The CILs program provides grants for agencies that are designed and operated within a local community by individuals with disabilities and provide an array of services. At a minimum, centers must provide core services (information and referral, independent living skills training, peer counseling, and individual and systems advocacy) and most centers also provide additional services such as community planning and decision making; school-based peer counseling, role modeling, and skills training; working with local governments and employers to open and facilitate employment opportunities; interacting with local, state, and federal legislators; and staging recreational events that integrate individuals with disabilities with their able-bodied peers.

- Community Action Agencies (CAA)

-

http://www.communityactionpartnership.com/

CAAs work to fight poverty at the local level. The Community Action Partnership was established in 1971 as the National Association of Community Action Agencies and is the national organization representing the interests of the 1,000 CAAs working to fight poverty at the local level.

- Community Development Block Grant Program (CDBG)

-

http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/comm_planning/communitydevelopment/programs

The CDBG program is a flexible program that provides communities with resources to address a wide range of unique community development needs. Beginning in 1974, the CDBG program is one of the longest continuously run programs at HUD.

The CDBG program works to ensure decent affordable housing, to provide services to the most vulnerable in our communities, and to create jobs through the expansion and retention of businesses. CDBG helps local governments tackle serious challenges facing their communities. The CDBG program has made a difference in the lives of millions of people and their communities across the nation.

- Office of Community Planning and Development (CPD)

-

http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/comm_planning

The Office of Community Planning and Development (CPD), U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) seeks to develop viable communities by promoting integrated approaches that provide decent housing, a suitable living environment, and expand economic opportunities for low and moderate income persons. The primary means is the development of partnerships among all levels of government and the private sector, including for-profit and non-profit organizations.

- Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC)

-

http://www.bt.cdc.gov/CERC/

Updated in 2006, this resource provides tools for communicating to the public, media, partners and stakeholders during an intense public health emergency.

CERC: For Leaders by Leaders

-

http://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/pdf/leaders.pdf

Developed in 2005, this course provides tools for speaking to the public, media, partners and stakeholders during an intense public-safety emergency, including terrorism.

Fundamentals of Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC)

-

http://info.med.yale.edu/eph/ycphp/cerc.html

This toolkit was developed by Yale Center for Public Health Preparedness to support a “train the trainer” program for state and local public health practitioners in public health emergency preparedness.

Emergency Risk Communication CDCynergy

-

http://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/CERConline/index.html

Based on CERC principles, ERC CDCynergy is a step-by-step tutorial and performance support tool to help federal, state, and local public health communicators systematically plan, implement, and evaluate emergency health communications. Contained on a single CD-ROM, ERC CDCynergy contains resources, examples, and tools for pre-event planning and preparation, communication response during and after an event, and advice from risk communication experts.

- Disability Preparedness Center

-

http://www.disabilitypreparedness.gov/

This disability preparedness web site provides practical information on how people with and without disabilities can prepare for an emergency. It also provides information for family members and service providers of people with disabilities. In addition, this site includes information for emergency planners and first responders to help them prepare for serving persons with disabilities.

- Diversity Rx

-

http://www.diversityrx.org/

A clearinghouse of information on how to meet the language and cultural needs of minorities, immigrants, refugees and other diverse populations seeking health care.

- Emergency Food and Shelter Programs (EFSP)

-

http://www.efsp.unitedway.org/efsp/website/index.cfm

The EFSP is an organization created to supplement the work of local social service organizations within the United States to help people in need of emergency assistance—shelter, food, and other support services.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

-

http://www.fema.gov/

FEMA’s continuing mission within the DHS is to lead the effort to prepare the nation for all hazards and effectively manage federal response and recovery efforts following any national incident. FEMA also initiates proactive mitigation activities, trains first responders, and manages the National Flood Insurance Program.

Resources for Individuals with Special Needs

http://www.fema.gov/plan/prepare/specialplans.shtm

Additional steps individuals with disabilities or special needs should take to prepare or respond to a disaster.

- First Hours: Communicating in the First Hours

-

http://www.bt.cdc.gov/firsthours/

The Office of Public Affairs of the HHS and the CDC have developed messages and other resources for federal, state, local, and tribal public health officials to use during a response to an emergency. The messages apply to all Category A Biological Agents, as classified by CDC, as well as messages about chemical and radiological events and suicide bombing and were written to be used by federal public health officials and to be adapted for the use of state and local public health officials during a terrorist attack or suspected attack.

- Use these messages as follows:

- To communicate with the public during a terrorist attack or a suspected attack

- To adapt for a specific event (These messages were written for fictitious situations, so assumptions were made about an event.)

- To provide information during the first hours of an event

- To save precious moments during the initial response time and to buy the time necessary for public health leaders to develop more specific messages

- Geographic Information System (GIS)

-

GIS is a system for creating, storing, analyzing and managing spatial data and associated attributes. In the strictest sense, it is a computer system capable of integrating, storing, editing, analyzing, sharing, and displaying geographically-referenced information. In a more generic sense, GIS is a tool that allows users to create interactive queries (user created searches), analyze the spatial information, and edit data. Geographic information science is the science underlying the applications and systems, taught as a degree program by several universities.

- Health Centers

-

http://bphc.hrsa.gov/

The diverse public and non-profit organizations and programs that receive federal funding under section 330 of the Public Health Service (PHS) Act, as amended by the Health Centers Consolidated Act of 1996 (P.L.104-299) and the Safety Net Amendments of 2002.

They include:

- Community Health Centers

- Migrant Health Centers

- Health Care for the Homeless Health Centers

- Primary Care Public Housing Health Centers

Health Centers are characterized by five essential elements that differentiate them from other providers:

- They must be located in or serve a high need community, i.e. “medically underserved areas” or “medically underserved populations;”

- They must provide comprehensive primary care services as well as supportive services such as translation and transportation services that promote access to health care;

- Their services must be available to all residents of their service areas, with fees adjusted upon patients’ ability to pay;

- They must be governed by a community board with a majority of members health center patients; and,

- They must meet other performance and accountability requirements regarding their administrative, clinical, and financial operations.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

-

http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/

The Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information (“Privacy Rule”) establishes, for the first time, a set of national standards for the protection of certain health information. The HHS issued the Privacy Rule to implement the requirement of the HIPAA. The Privacy Rule standards address the use and disclosure of individuals’ health information—called “protected health information” by organizations subject to the Privacy Rule—called “covered entities,” as well as standards for individuals’ privacy rights to understand and control how their health information is used. Within HHS, the Office for Civil Rights has responsibility for implementing and enforcing the Privacy Rule with respect to voluntary compliance activities and civil money penalties.

A major goal of the Privacy Rule is to assure that individuals’ health information is properly protected while allowing the flow of health information needed to provide and promote high quality health care and to protect the public’s health and well-being. The rule strikes a balance that permits important uses of information, while protecting the privacy of people who seek care and healing. Given that the health care marketplace is diverse, the rule is designed to be flexible and comprehensive to cover the variety of uses and disclosures that need to be addressed.

- Indian Health Service (IHS)

-

http://www.ihs.gov/

HIS IHS is the federal health program to promote healthy American Indian and Alaska Native people, communities, and cultures.

- Meals On Wheels Association of America (MOWAA)

-

http://www.mowaa.org/

The oldest and largest organization in the United States representing those who provide meal services to people in need, MOWAA works toward the social, physical, nutritional, and economic betterment of vulnerable Americans.

The MOWAA provides the tools and information its programs need to make a difference in the lives of others. It also gives cash grants to local senior meal programs throughout the country to assist in providing meals and other nutrition services.

- Mental Health America (MHA)

-

http://www.nmha.org/ or http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/

Formerly National Mental Health Association (NMHA), a nonprofit organization addressing all aspects of mental health and mental illness.

- Modern Language Association (MLA) Language Map

-

http://www.mla.org/map_main

The MLA Language Map and its Data Center provide information about more than 47,000,000 people in the United States who speak languages other than English at home. It uses data from the 2000 U.S. Census to display the locations and numbers of speakers of 30 languages in the United States.

- National Assessment of Adult Literacy

-

http://nces.ed.gov/naal/

The 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy is a nationally representative assessment of English literacy among American adults age 16 and older. Sponsored by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), NAAL is the nation’s most comprehensive measure of adult literacy since the 1992 National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS).

Health Literacy Component

-

http://nces.ed.gov/naal/health.asp

-

Introduces the first-ever national assessment of adults’ ability to use their literacy skills in understanding health-related materials and forms.

- National Area Health Education Center (AHEC) Organization (NAO)

-

http://www.nationalahec.org/home/index.asp

The national organization to support and advance the Area Health Education Center (AHEC)/Health Education Training Center (HETC) network in improving the health of individuals and communities by transforming health care through education.

There are currently 50 AHEC programs with more than 200 centers and a dozen HETCs operating in almost every state and the District of Columbia. Approximately 120 medical schools and 600 nursing and allied health schools work collaboratively with AHECs and HETCs to improve health for underserved and under-represented populations.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)

-

http://www.nami.org/

The nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization dedicated to improving the lives of persons living with serious mental illness and their families. Founded in 1979, NAMI has become the nation’s voice on mental illness, a national organization including NAMI organizations in every state and in over 1,100 local communities across the country who join together to meet the NAMI mission through support, education, and advocacy.

- National Association of the Deaf (NAD)

-

http://www.nad.org/

An organization that promotes, protects, and preserves the rights of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals.

- National Association on Alcohol, Drugs, and Disability (NAADD)

-

http://www.naadd.org/

NAADD promotes awareness and education about substance abuse among people with co-existing disabilities.

- National Association of Counties (NACo)

-

http://www.naco.org

NACo is the only national organization that represents county governments in the United States. NACo understands the importance of strong public-private partnerships and is committed to assisting counties and businesses explore new, innovative ways of working together.

- National Association of Regional Councils (NARC)

-

http://www.narc.org/

NARC is a non-profit organization that represents pro-active, multi-functional, full-service organizations that serve local units of government. Members are local elected officials and professionals who work with community leaders and citizens in several core areas, such as transportation, community and economic development, environmental quality, homeland security and emergency preparedness.

- National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC)

-

http://www11.georgetown.edu/research/gucchd/nccc/

The mission of the NCCC is to increase the capacity of health and mental health programs to design, implement, and evaluate culturally and linguistically competent service delivery systems.

- National Center for Cultural Competence Database

-

https://www.cme.ucsf.edu/culturalresources.aspx

The NCCC Resource Database includes of a wide range of resources on cultural and linguistic competence (e.g. demographic information, policies, practices, articles, books, research initiatives and findings, curricula, multimedia materials and Websites, etc.). The NCCC uses specific review criteria for the inclusion of these resources. As part of the NCCC’s web-based technical assistance, a selected searchable bibliography of these resources is made available online. The database is not an exhaustive listing and it is updated on a regular basis.

- National Center for Frontier Communities

-

http://www.frontierus.org/index-current.htm

The only national organization dedicated to the smallest and most geographically isolated communities in the United States—the frontier. The Center operates a clearinghouse for Frontier communities as a central point of contact for referrals, information exchange, and networking among geographically separated communities.

- National Council on Aging (NCOA)

-

http://www.ncoa.org

NCOA is a nonprofit service and advocacy organization headquartered whose mission is to improve the lives of older Americans.

- National Council on Disabilities (NCD)

-

http://www.ncd.gov/

NCD is an independent federal agency that works to enhance the quality of life for all Americans with disabilities and their families.

- National Council on Independent Living (NCIL)

-

http://www.ncil.org/

NCIL is a membership organization that advances independent living and the rights of those with disabilities.

- National Council of La Raza (NCLR)

-

http://www.nclr.org/

The NCLR is the largest national Latino civil rights and advocacy organization in the United States. NCLR works to improve opportunities for Hispanic Americans.

- National Council on Interpreting in Health Care (NCIHC)

-

http://www.ncihc.org

NCIHC is committed to promoting ethics, standards and quality for medical interpreters in the United States.

- National Family Association for the Deaf-Blind (NFADB)

-

http://www.nfadb.org/

A nonprofit association that works to ensure deaf and/or blind individuals are entitled to the same opportunities as other members of the community.

- National Indian Health Board

-

http://www.nihb.org

The National Indian Health Board advocates on behalf of Tribal Governments and American Indians/Alaska Natives in their efforts to provide quality health care.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)NOAA Weather Radio All Hazards (NWR)

-

http://www.weather.gov/nwr/

A nationwide network of radio stations broadcasting continuous weather information directly from the nearest National Weather Service office. NWR broadcasts official Weather Service warnings, watches, forecasts and other hazard information 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Working with the Federal Communication Commission’s Emergency Alert System, NWR is an “All Hazards” radio network, making it a single source for comprehensive weather and emergency information. In conjunction with federal, state, and local emergency managers and other public officials, NWR also broadcasts warning and post-event information for all types of hazards—including natural (such as earthquakes or avalanches), environmental (such as chemical releases or oil spills), and public safety (such as AMBER alerts or 911 Telephone outages).

- National Organization on Disability (NOD)

-

http://www.nod.org/

The mission of the National Organization on Disability (NOD) is to expand the participation and contribution of America’s 54 million men, women, and children with disabilities in all aspects of life. By raising disability awareness through programs and information, together we can work toward closing the participation gaps.

- National Rural Health Association (NRHA)

-

http://www.ruralhealthweb.org/

NRHA is a national nonprofit membership organization. NRHA’s mission is to improve the health and wellbeing of rural Americans and to provide leadership on rural health issues through advocacy, communications, and education.

- National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS)

-

http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=15

The standards are intended to be inclusive of all cultures and not limited to any particular population group or sets of groups; however, they are especially designed to address the needs of racial, ethnic, and linguistic population groups that experience unequal access to health services. Ultimately, the aim of the standards is to contribute to the elimination of racial and ethnic health disparities and to improve the health of all Americans.

There are 14 CLAS standards organized by themes:

- Culturally Competent Care (Standards 1-3),

- Language Access Services (Standards 4-7)

- Organizational Supports for Cultural Competence (Standards 8-14)

They include three types of standards of varying stringency:

- CLAS mandates are current federal requirements for all recipients of Federal funds (Standards 4, 5, 6, and 7).

- CLAS guidelines are activities recommended by the Office of Minority Health (OMH) for adoption as mandates by federal, state, and national accrediting agencies (Standards 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13).

- CLAS recommendations are suggested by OMH for voluntary adoption by health care organizations (Standard 14).

Additional resources to help you apply the CLAS standards:

http://www.diversityrx.org/

- National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC)

http://www11.georgetown.edu/research/gucchd/nccc/

- National States Geographic Information Council (NSGIC)

-

http://www.nsgic.org/

NSGIC is committed to efficient and effective government through the prudent adoption of geospatial information technologies (GIT). Members of NSGIC include senior state GIS managers and coordinators.

- National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (NVOAD)

-

http://www.nvoad.org/

NVOAD is an organization that coordinates planning efforts by many voluntary organizations responding to disaster. NVOAD is not itself a service delivery organization. Instead, it upholds the privilege of its members to independently provide relief and recovery services, while expecting them to do so cooperatively. NVOAD is committed to the idea that the best time to train, prepare, and become acquainted with each other is prior to the actual disaster response. Organizations and agencies that wish to become NVOAD members go through an application process and need to demonstrate their capability to work within the parameters agreed to by the members of NVOAD.

- New America Media (NAM)

-

http://www.newamericamedia.org

NAM is the country’s first and largest national collaboration of ethnic news organizations. Founded by the nonprofit Pacific News Service in 1996, NAM is headquartered in California, where ethnic media are the primary source of news and information for over half of the state’s new ethnic majority.

- NOAA Weather Radio

-

See National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration.

- Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA)

-

http://www.pva.org

Congressionally chartered veterans service organization with a unique expertise on the special needs of veterans.

- Pew Hispanic Center

-

http://pewhispanic.org/

The Pew Hispanic Center is a nonpartisan research organization that works to improve understanding of the U.S. Hispanic population.

- Refugee Health Promotion & Disease Prevention (RHPDP) Initiative/Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR)

-

http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/orr/benefits/health.htm

An approach to health and mental health to increase awareness and interest in health promotion and disease prevention programs targeting refugees, and provide information and tools to assist organizations in related activities and services. The overall objective of this initiative is to increase the health and well-being of high risk refugee populations in the United States.

- Regional Councils

-

http://www.narc.org/

Regional Councils are multi-service entities with state and locally defined boundaries that may deliver federal, state, and local programs while functioning as planning organizations. They are accountable to local units of government and typically work in comprehensive and transportation planning, economic development, workforce development, the environment, services for the elderly, and clearinghouse functions. According to the National Association of Regional Councils (NARC), nearly half of all MPOs operate as part of a Regional Council.

- Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID)

-

http://www.rid.org/

A national membership organization of professionals who provide sign language interpreting/ transliterating services for deaf and hard of hearing persons.

- Reverse 911

-

http://www.cassidiancommunications.com/notification-systems

REVERSE 911® is a communications solution that uses a patented combination of database and GIS mapping technologies to deliver outbound notifications. Users can quickly target a precise geographic area and saturate it with thousands of calls per hour. The system’s interactive technology provides immediate interaction with recipients and aids in rapid response to specific needs.

Users can also create a list of individuals with common characteristics (such as a Neighborhood Crime Watch group or emergency responder teams) and contact them with helpful information as needed. REVERSE 911® is used effectively in thousands of communities, counties, commercial businesses, schools and non-profit organizations to dramatically improve the lines of communication to the general population and targeted groups.

- Snapshots of Data for Communities Nation-Wide (SNAPS)

-

SNAPS provides local level community profile information nation-wide. It can be browsed by county and state and searched by zip code. SNAPS serves as a valuable tool when responding to public health emergencies at the state, tribal, and local levels. It provides a “snapshot” of key variables for consideration in guiding and tailoring health education and communication efforts to ensure diverse audiences receive critical public health messages that are accessible, understandable, and timely.

Online access to SNAPS is available at:

-

http://www.bt.cdc.gov/snaps/.

Additional information and SNAP CD-ROMS can be requested by contacting the ECS Community Health Education Team at 404-639-0568.

- Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)

-

http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic

WIC serves to safeguard the health of low-income women, infants, and children up to age 5 who are at nutritional risk by providing nutritious foods to supplement diets, information on healthy eating, and referrals to health care.

- The Sphere Project

-

http://www.sphereproject.org

Launched in 1997 by a group of humanitarian Non-governmental Organizations and the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement, Sphere has an international scope and is based on two core beliefs: first, that all possible steps should be taken to alleviate human suffering arising out of calamity and conflict, and second, that those affected by disaster have a right to life with dignity and therefore a right to assistance. Sphere is three things: a handbook outlining minimum standards of support, a broad process of collaboration, and an expression of commitment to quality and accountability.

- Strategic National Stockpile (SNS)

-

http://www.bt.cdc.gov/stockpile

CDC’s Strategic National Stockpile is a national repository of antibiotics, chemical antidotes, antitoxins, life-support medications, IV administration, airway maintenance supplies, and medical/surgical items. The SNS is designed to supplement and re-supply state and local public health agencies in the event of a national emergency anywhere and at anytime within the U.S. or its territories. Once federal and local authorities agree that the SNS is needed, medicines will be delivered to any state in the U.S. within 12 hours. Each state has plans to receive and distribute SNS medicine and medical supplies to local communities as quickly as possible.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

-

http://www.samhsa.gov

A public health agency within the HHS, responsible for improving the accountability, capacity and effectiveness of the nation’s substance abuse prevention, addictions, treatment, and mental health services delivery system.

- Tips for First Responders (2nd Edition)

-

http://cdd.unm.edu/dhpd/tips.asp

This booklet provides tips for first responders on dealing with specific populations, including: seniors, people with service animals, mobility impairments, autism, deaf or hard of hearing, blind or visually impaired, cognitive disabilities, multiple chemical sensitivities, and mentally ill.

- Trust for America’s Health (TFAH)

-

http://www.tfah.org

TFAH is a non-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to saving lives by protecting the health of every community and working to make disease prevention a national priority.

TFAH released the fourth annual report: Ready or Not? Protecting the Public’s Health from Disease, Disasters, and Bioterrorism in December 2006.

http://www.healthyamericans.org/reports/bioterror06/BioTerrorReport2006.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau

-

http://www.census.gov

Part of the U.S. Department of Commerce, the U.S. Census enumerates the population once every ten years, and collects statistics about the nation, its people, and economy.

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

-

http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis

Responsible for the administration of immigration and naturalization adjudication functions and establishing immigration services, policies, and priorities.

- The United Way

-

http://www.unitedway.org

The United Way is an overarching organization that mobilizes local leaders and their communities to identify and address local human needs.

- Women and Infants Service Package (WISP)

-

National Working Group for Woman and Infant Needs in Emergencies in the United States

http://www.whiteribbonalliance.org/wra/assets/file/WISP.Final.07.27.07.pdf

The goal of WISP is to ensure that the health care needs of pregnant women, new mothers, fragile newborns, and infants are adequately met during and after a disaster. The guidelines are intended to aid emergency planners and managers, maternal and child health organizations, professional associations, and federal, state and local government agencies.

The capacity to reach every person in a community is one of the major goals for emergency preparedness and response. The goal of emergency health communication is to rapidly get the right information to the entire population so that they are able to make the right choices for their health and safety. To do this, a community must know what subgroups make up its population, where the people in these groups live and work, and how they best receive information. Although knowing this type of information might seem obvious, many jurisdictions have not yet begun the process to define or locate their at-risk populations.

The capacity to reach every person in a community is one of the major goals for emergency preparedness and response. The goal of emergency health communication is to rapidly get the right information to the entire population so that they are able to make the right choices for their health and safety. To do this, a community must know what subgroups make up its population, where the people in these groups live and work, and how they best receive information. Although knowing this type of information might seem obvious, many jurisdictions have not yet begun the process to define or locate their at-risk populations. Regardless of terminology, trust plays a critical role in reaching at-risk populations. Reaching people through trusted channels has shown to be much more effective than through mainstream channels. For some people, trusted information comes more readily from within their communities than from external sources.

Regardless of terminology, trust plays a critical role in reaching at-risk populations. Reaching people through trusted channels has shown to be much more effective than through mainstream channels. For some people, trusted information comes more readily from within their communities than from external sources. One lesson learned from events since 2001, especially Hurricane Katrina in 2005, is that traditional methods of communicating health and emergency information often fall short of the goal of reaching everyone in a community. Although a great deal of work has been done, public engagement for emergency response planning remains low. Other reports and legislation have also acknowledged this challenge as indicated below.

One lesson learned from events since 2001, especially Hurricane Katrina in 2005, is that traditional methods of communicating health and emergency information often fall short of the goal of reaching everyone in a community. Although a great deal of work has been done, public engagement for emergency response planning remains low. Other reports and legislation have also acknowledged this challenge as indicated below. When enacted in December 2006, the

When enacted in December 2006, the

Chinese or simply does not read or understand English well, the communication barrier is a language or literacy issue and many of the strategies for message adaptation can be the same. Instead of translating emergency messages into 126 languages spoken in a community, public health departments have initiated pilot efforts to convey crucial information in simple, picture-based messages that are easily understood by everyone.

Chinese or simply does not read or understand English well, the communication barrier is a language or literacy issue and many of the strategies for message adaptation can be the same. Instead of translating emergency messages into 126 languages spoken in a community, public health departments have initiated pilot efforts to convey crucial information in simple, picture-based messages that are easily understood by everyone. Start with economic disadvantage. If resources permit a community to address only one at-risk population characteristic, using poverty as a criteria may help reach a large number of people.

Start with economic disadvantage. If resources permit a community to address only one at-risk population characteristic, using poverty as a criteria may help reach a large number of people.

According to the

According to the  People can be isolated if they live in rural areas or in the middle of a densely populated urban core. There are many ways people might be considered isolated, including:

People can be isolated if they live in rural areas or in the middle of a densely populated urban core. There are many ways people might be considered isolated, including:

Although many elderly people are competent and able to access health care or provide for themselves in an emergency, chronic health problems, limited mobility, blindness, deafness, social isolation, fear, and reduced income put older adults at an increased risk during an emergency.

Although many elderly people are competent and able to access health care or provide for themselves in an emergency, chronic health problems, limited mobility, blindness, deafness, social isolation, fear, and reduced income put older adults at an increased risk during an emergency. Begin by investigating and analyzing available data gathered by others to shed light on different population groups in your community. You can use many sources of population statistics from the national level down to local agencies. This quantitative data, previously gathered by others, will help you begin the process and build a “snapshot” of your community. Some resources that are available to help you with creating this snapshot include:

Begin by investigating and analyzing available data gathered by others to shed light on different population groups in your community. You can use many sources of population statistics from the national level down to local agencies. This quantitative data, previously gathered by others, will help you begin the process and build a “snapshot” of your community. Some resources that are available to help you with creating this snapshot include:

You probably already know who some at-risk populations are and how to reach them because they are enrolled in programs and receive services from your agency. State and local public health departments, for example, know women who are connected through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and generally know how to get in touch with them; or they know how to contact daycare providers who can help locate parents and guardians in an emergency.

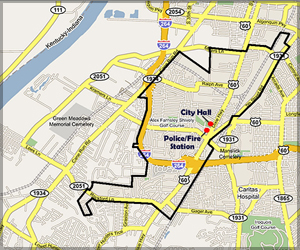

You probably already know who some at-risk populations are and how to reach them because they are enrolled in programs and receive services from your agency. State and local public health departments, for example, know women who are connected through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and generally know how to get in touch with them; or they know how to contact daycare providers who can help locate parents and guardians in an emergency. If you do not have access to or are unable to use GIS software, post a map of your community on a wall. Use the census and other data you have collected in the "define" phase and information gathered from community collaborators to determine where your at-risk populations might be found. Use pushpins or markers for a visual representation.

If you do not have access to or are unable to use GIS software, post a map of your community on a wall. Use the census and other data you have collected in the "define" phase and information gathered from community collaborators to determine where your at-risk populations might be found. Use pushpins or markers for a visual representation. Collaborate with your partners to find the places where your identified populations gather. This will help you to locate individuals and groups within these populations. People who share important aspects of their lives gravitate socially and geographically to traditional gathering places or venues where they feel comfortable.

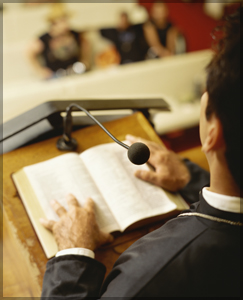

Collaborate with your partners to find the places where your identified populations gather. This will help you to locate individuals and groups within these populations. People who share important aspects of their lives gravitate socially and geographically to traditional gathering places or venues where they feel comfortable.

This lack of credibility underscores why it is so important to build your network, or COIN, of trusted spokespersons with whom your at-risk populations will identify and trust. These individuals might not serve in an official capacity or be known to public health and emergency providers yet, but they can serve as a channel of information and become a cadre of leaders in emergencies. The same qualities that make them leaders in their communities often make them willing to serve as a liaison between health professionals and at-risk populations before and during an emergency.

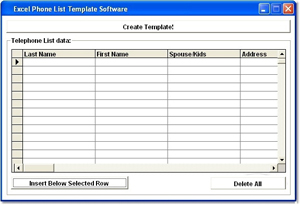

This lack of credibility underscores why it is so important to build your network, or COIN, of trusted spokespersons with whom your at-risk populations will identify and trust. These individuals might not serve in an official capacity or be known to public health and emergency providers yet, but they can serve as a channel of information and become a cadre of leaders in emergencies. The same qualities that make them leaders in their communities often make them willing to serve as a liaison between health professionals and at-risk populations before and during an emergency. Include trusted sources in meetings and planning sessions with other community organizations and service providers. Add them to your database, capturing their contact information and how they prefer to be reached. As you build your network of trusted sources, map their locations in your community so you can begin to get a visual representation of the network you are developing.

Include trusted sources in meetings and planning sessions with other community organizations and service providers. Add them to your database, capturing their contact information and how they prefer to be reached. As you build your network of trusted sources, map their locations in your community so you can begin to get a visual representation of the network you are developing. Ongoing engagement of your partners and representatives from community organizations is important throughout each phase of this process. You can host a meeting or conference call with the representatives of community organizations that you have already identified to discuss the issues involved as you locate at-risk populations. Talking with representatives of community organizations that serve at-risk populations, including those that address human service needs as well as community needs, is essential to determine which organizations can help you the most. Not every community representative will have a role to play in the "locate" phase, but they can be valuable connections to reach groups and to disseminate health or emergency information. This dialogue will enable you to meet community collaborators who can help you learn where to locate at-risk population groups. Ask community collaborators to explain:

Ongoing engagement of your partners and representatives from community organizations is important throughout each phase of this process. You can host a meeting or conference call with the representatives of community organizations that you have already identified to discuss the issues involved as you locate at-risk populations. Talking with representatives of community organizations that serve at-risk populations, including those that address human service needs as well as community needs, is essential to determine which organizations can help you the most. Not every community representative will have a role to play in the "locate" phase, but they can be valuable connections to reach groups and to disseminate health or emergency information. This dialogue will enable you to meet community collaborators who can help you learn where to locate at-risk population groups. Ask community collaborators to explain: An overarching organization is the lead organization that might partner with or provide funding to many direct service providers. The service provider organizations are a more direct link to the populations they serve. You first contacted overarching organizations and government agencies in the “define” phase. These organizations can now serve as a link to service providers, providing detailed information and saving you time and resources.

An overarching organization is the lead organization that might partner with or provide funding to many direct service providers. The service provider organizations are a more direct link to the populations they serve. You first contacted overarching organizations and government agencies in the “define” phase. These organizations can now serve as a link to service providers, providing detailed information and saving you time and resources. As you expand your list of organizations and contacts, the following tips might be helpful:

As you expand your list of organizations and contacts, the following tips might be helpful: If there is a college or university in your area, you can contact the student affairs department to ask for information. Often a person belonging to the group will be the best source of information.

If there is a college or university in your area, you can contact the student affairs department to ask for information. Often a person belonging to the group will be the best source of information. The success of your network is built upon trust. Demonstrate your commitment to COIN members by having clear policies for how contact information will be used and by clearly defining confidentiality issues at the start of your relationship with each member. As keeper of this important contact information, decide ahead of time if you would be willing to disseminate messages on behalf of other partners during normal, non-emergency times, and include policies and procedures for non-emergency communications.

The success of your network is built upon trust. Demonstrate your commitment to COIN members by having clear policies for how contact information will be used and by clearly defining confidentiality issues at the start of your relationship with each member. As keeper of this important contact information, decide ahead of time if you would be willing to disseminate messages on behalf of other partners during normal, non-emergency times, and include policies and procedures for non-emergency communications. In an emergency, messages must not only inform and educate, but they must also mobilize people to follow public health directives. People are reached by using the languages they speak in dissemination methods such as television, radio, newspaper, bill inserts, or fliers. Messages are also spread by word-of-mouth (often the most effective communication method) and through social and community networks. For people to act, they must understand the message, believe the messenger is credible and trustworthy, and have the capacity to respond.

In an emergency, messages must not only inform and educate, but they must also mobilize people to follow public health directives. People are reached by using the languages they speak in dissemination methods such as television, radio, newspaper, bill inserts, or fliers. Messages are also spread by word-of-mouth (often the most effective communication method) and through social and community networks. For people to act, they must understand the message, believe the messenger is credible and trustworthy, and have the capacity to respond.

An important next step is to use community assessment techniques (surveys and focus groups) to reveal in-depth details on the barriers and specific communication needs of at-risk populations in your community. Although these techniques can be the same used in research, you can use them for local program purposes not for creating general knowledge. Policies and procedures should be followed to ensure the privacy of the participants and the information collected.

An important next step is to use community assessment techniques (surveys and focus groups) to reveal in-depth details on the barriers and specific communication needs of at-risk populations in your community. Although these techniques can be the same used in research, you can use them for local program purposes not for creating general knowledge. Policies and procedures should be followed to ensure the privacy of the participants and the information collected. This information can be obtained by asking leading questions like:

This information can be obtained by asking leading questions like: Before you conduct focus groups or community roundtables, check with your COIN and within your own agency to determine if these have already been done. Also consider the best ways to access your intended population. For example, if your target demographic is the elderly, conducting a focus group might not be effective because elderly people might have transportation or mobility issues that prohibit them from attending a focus group. This population may also mistrust people they do not know and worry about their personal safety.7

Before you conduct focus groups or community roundtables, check with your COIN and within your own agency to determine if these have already been done. Also consider the best ways to access your intended population. For example, if your target demographic is the elderly, conducting a focus group might not be effective because elderly people might have transportation or mobility issues that prohibit them from attending a focus group. This population may also mistrust people they do not know and worry about their personal safety.7 In these instances, a telephone interview might be a more appropriate data collection method if trusted members of the community adequately prepare this population for such outreach. Telephone surveys are not without limitations and do not capture those without telephones, are possibly biased due to mobile phone use, and have a potentially low response rate because of caller identification and answering machines. As an alternative, a written survey delivered by a trusted source, such as a Meals on Wheels provider or a family member, could be an effective way to encourage participation.

In these instances, a telephone interview might be a more appropriate data collection method if trusted members of the community adequately prepare this population for such outreach. Telephone surveys are not without limitations and do not capture those without telephones, are possibly biased due to mobile phone use, and have a potentially low response rate because of caller identification and answering machines. As an alternative, a written survey delivered by a trusted source, such as a Meals on Wheels provider or a family member, could be an effective way to encourage participation. As you review your findings from the "define" and "locate" phases of this process, along with your recent focus groups and surveys, you might see common characteristics and needs that will enable you to create a list of key findings for each population. Look for common themes and emerging patterns that relate to reaching at-risk populations with messages they understand and to which they can respond.

As you review your findings from the "define" and "locate" phases of this process, along with your recent focus groups and surveys, you might see common characteristics and needs that will enable you to create a list of key findings for each population. Look for common themes and emerging patterns that relate to reaching at-risk populations with messages they understand and to which they can respond. Your assessment provides the basis for understanding the cultural and linguistic characteristics of your community and the communication barriers faced by at-risk populations. Such findings will serve as the basis for developing communication strategies that overcome communication barriers and convey information that is understandable and relevant to members of the diverse populations.

Your assessment provides the basis for understanding the cultural and linguistic characteristics of your community and the communication barriers faced by at-risk populations. Such findings will serve as the basis for developing communication strategies that overcome communication barriers and convey information that is understandable and relevant to members of the diverse populations. As part of your ongoing efforts to strengthen your local community’s capacity to respond to a public health emergency, you can conduct workshops with representatives of at-risk populations and community leaders who are already committed to participating in your agency’s outreach work. The workshops:

As part of your ongoing efforts to strengthen your local community’s capacity to respond to a public health emergency, you can conduct workshops with representatives of at-risk populations and community leaders who are already committed to participating in your agency’s outreach work. The workshops: Collaborate with community organizations or bring COIN members to the planning table to address the needs of at-risk populations in your agency’s all-hazards emergency preparedness plan by:

Collaborate with community organizations or bring COIN members to the planning table to address the needs of at-risk populations in your agency’s all-hazards emergency preparedness plan by:

As your COIN continues to grow, you will want to ensure that you keep in touch with the members and that you are incorporating their input into your existing communication and emergency operations plans.

As your COIN continues to grow, you will want to ensure that you keep in touch with the members and that you are incorporating their input into your existing communication and emergency operations plans. Enhance your communication plan to reach at-risk populations. Using key findings from your surveys, focus groups, and other searches, along with the information in your database, you can enhance your existing communication plan to include at-risk population groups and to designate the appropriate, trusted spokespersons. Be sure to include members of the at-risk populations in your planning sessions. Encourage them to provide input so that your communication plan is feasible and appropriate.

Enhance your communication plan to reach at-risk populations. Using key findings from your surveys, focus groups, and other searches, along with the information in your database, you can enhance your existing communication plan to include at-risk population groups and to designate the appropriate, trusted spokespersons. Be sure to include members of the at-risk populations in your planning sessions. Encourage them to provide input so that your communication plan is feasible and appropriate. In a community, this systematic process can be used by all emergency planners to work together to define, locate and reach at-risk populations. It is hoped that everyone exploring the process will work to connect with one another and to coordinate their activities. Now that the process is complete, you will need to continue strengthening the relationships that you have developed.

In a community, this systematic process can be used by all emergency planners to work together to define, locate and reach at-risk populations. It is hoped that everyone exploring the process will work to connect with one another and to coordinate their activities. Now that the process is complete, you will need to continue strengthening the relationships that you have developed. Expand your scope. Once you have been able to successfully define, locate, and reach members of your initial at-risk population groups, you can expand your initiative to include more groups using the same steps you followed in each phase of this process.

Expand your scope. Once you have been able to successfully define, locate, and reach members of your initial at-risk population groups, you can expand your initiative to include more groups using the same steps you followed in each phase of this process.